Education 540: Yes Smartphones Need to Go...

Aug 13, 2024 10:40AM ● By Martin Davis

James Monroe High School started the 2023-24 school year with a bang. Administration and teachers were in sync on banning the use of cellphones during class, and in the hallways.

The problem, teachers soon realized, was that students still had them on their persons. While many adults who didn’t grow up with smartphones have the discipline necessary to have their phones on them but not use it, many students don’t.

These little, yet powerful, personal computers are more than just a handy dopamine rush. They have become a dependable source of affirmation that students crave. And students, unless physically separated from them, are going to find a way to use them.

The tell-tell signs were there from day one.

As a teacher, I watched while students buried their heads in their arms, with their phones in their laps, trying to avoid drawing attention to themselves.

Students using blankets and bookbags to build mini-forts to hide behind, each fort equipped with a personal smart phone.

I’ve watched as students tried to blend phone with textbook or notebook, to give the guise of working when they’re really doomscrolling.

Phones are placed on the floor between the feet, Netflix playing.

The level of creativity could, at times, prove rather remarkable. One student, when asked to put their phone away, dutifully stuck the phone in their pocket. Not looking closely, I assumed it was put away, only to realize shortly thereafter that the pocket had a hole that was covered with what appeared to be a sheer stocking. Thus, allowing the student to access and use their phone.

More Than Annoyance

At its most basic level, smartphone use was a discipline issue. The rules were clear, and the students weren’t following them.

By the end of the first quarter, however, it had become apparent that the discipline issue was the least of the problems smartphones were creating.

Many students, simply put, were addicted. A study by Common Sense Media in 2016 found that half of students were addicted to their smartphones. Those percentages are surely higher now.

When it came down to me and what was happening in class, that bundle of microchips was going to win every time.

Worse than the addiction, however, is what phones were doing to students’ ability to interact with me, and their classmates.

As a teacher who instructs using the Socratic method — an approach that has the teacher asking questions, students responding, and teachers then challenging those answers — I’m not unfamiliar with the pregnant pause. That uncomfortable moment between asking a question and waiting for someone, anyone, to speak.

Too often, the pregnant pause became a game of waiting one another out a la Robin Williams and Matt Damon in Good Will Hunting.

In other words, students weren’t displaying the normal unease associated with taking a risk by answering a question for fear that others may laugh, or the teacher may gently suggest they had missed the point entirely.

What I was observing was an inability to speak because the questions had no black-and-white answers, and students had little to no experience dealing with the ambiguity that defines higher thinking.

Just one example will suffice.

While discussing the Communist Manifesto with a sociology class, I asked: “What do you make of Marx’s distinction between communists and the proletariat class as a whole?”

Eyes shifted down. Fingers reached for phones. And a silence fell over the room.

When students did finally speak, it was to read word-for-word from the Manifesto what Marx had written (text we had moments before read collectively as a class). Pushed to explain what the words they cited meant, they couldn’t.

Evidence Building for Smartphone’s Damaging Student Learning

The students’ inability to wrestle with the Marxian text is what one would expect, based on the abundance of literature that has been building over the past decade about smartphones’ destructive effects on students’ ability to concentrate and process information.

One of the earliest studies was conducted in England by Louis-Philippe Beland and Richard Murphy. Their research paper, “Ill Communication: Technology, Distraction & Student Performance” noted that:

“Mobile phones can be a source of great disruption in workplaces and classrooms, as they provide individuals with access to texting, games, social media and the Internet. Given these features, mobile phones have the potential to reduce the attention students pay to classes and can therefore be detrimental to learning.”

Comparing school districts in Birmingham, London, Leicester, and Manchester, the researchers produced some startling results that highlighted the disruptive power of smartphones.

Performance on high-stakes tests following cell phone bans in those districts improved student test scores by 6.41% of a standard deviation. More eye-opening was the finding that the improvement was 14.23% of a standard deviation among the most disadvantaged and underachieving pupils.

The conclusion?

The results suggest that low-achieving students are more likely to be distracted by the presence of mobile phones, while high achievers can focus on the classroom regardless of the mobile phone policy.

Soon, districts across the globe were falling in line, banning smartphones in classrooms and schools. Just last year, England announced a total ban.

Beland, who authored the 2015 study, took to the pages of The Conversation in 2021 to track the ongoing research since his groundbreaking study. His article, “Banning mobile phones in schools can improve students’ academic performance. This is how we know,” not surprisingly highlights a bevy of research that confirms what he initially observed in 2015.

Simple Fix to a Complex Problem?

In the face of overwhelming evidence like this, it’s easy to understand why districts across the country, as well as in Virigina, King William, and locally in Stafford are either banning phones or moving in that direction.

Yet, there is an inherent contradiction in these moves that has largely been ignored. Adults are as addicted to their phones as the students that they’re sending to our public and private schools.

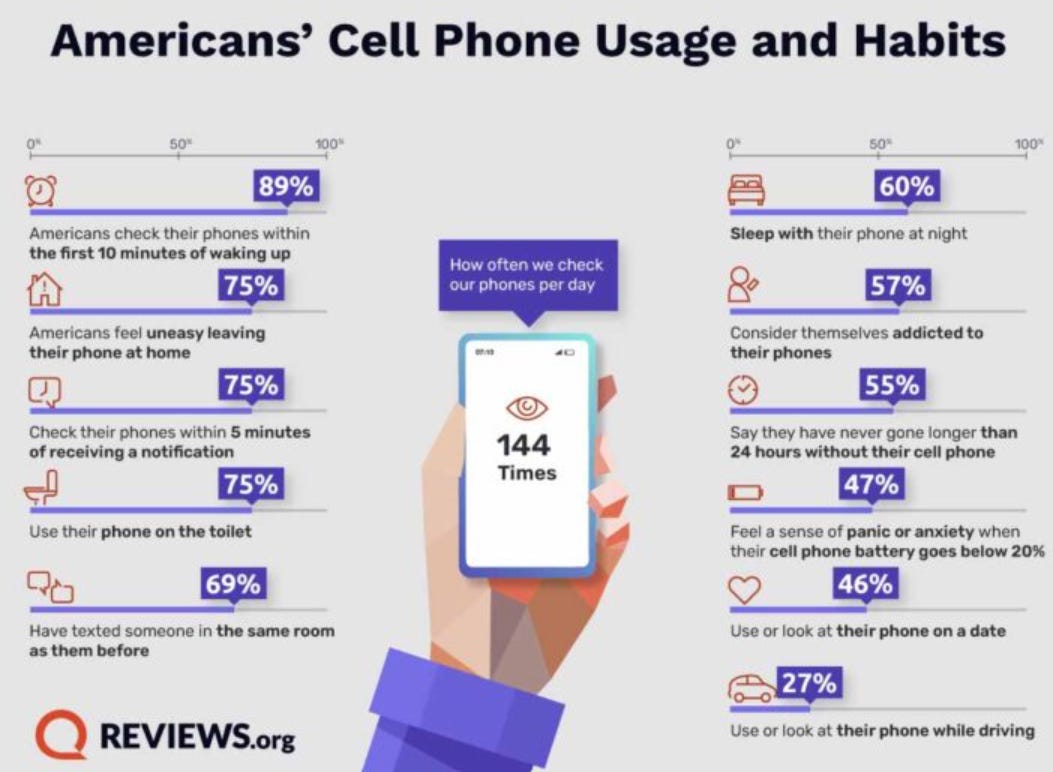

How addicted are we? Almost half of us say we get panicky when our phone battery drops below 20%. Three-fourths of us check our phones within five minutes of receiving a notification. The same percentage use our phones in the bathroom. And there are more disturbing numbers, as the chart above shows.

This research made me curious about my own phone usage. The results were humbling.

During the hours that I was in school, I accessed my phone less than 20 minutes (usually at lunch, or during planning). But outside of school? I was averaging about 5 hours a day.

Addicted? I’d argue no. That usage was tied to my work with the FXBG Advance, which I focused on after classes were over and until I went to bed — often way later than I’d care to admit.

The point? The tool itself isn’t the issue. It’s how the tool is used.

That’s the point that Michael Horn makes for Education Next in his article “Ban the Cellphone Ban”:

There’s an irony here. These bans are proliferating even as there are more useful, engaging, and instructionally sound mobile-learning applications than ever before. That suggests that cellphone bans, while useful in many school settings, shouldn’t be universal. We risk barring teachers, schools, and districts from productively using these apps to drive learning gains.

He acknowledges that smartphones can be an issue in classes, such as ones taught Socratically. However, a universal ban to support one teaching model is an ill-suited approach to dealing with student attention spans.

“… cellphone bans,” he argues, are following the larger trend of banning many things in schools—from books to speakers to certain kinds of speech or topics of debate. Cellphones may make for another easy bogeyman, but blanket bans are ill-informed and regressive.”

Though Horn has a case, and a blanket ban can feel Draconian, he misses an important point.

Students don’t know how to use the tool, and increasingly, neither do the adults who are teaching them. The adults, it’s becoming clear, are every bit as addicted as the students who we criticize for modeling the very smartphone habits we display.

Smartphones, Standardized Tests Deter Abstract Learning

We’re now a full generation into young adults who have had smartphones in their hands a significant portion of their lives. We’re also a full generation into young adults whose experience of education is defined by standardized testing.

The two go hand-in-hand. Standardized testing prizes rote memory and black-and-white answers above all else. Smartphones are a natural ally of that approach.

Consequently, many parents today have had their ability to comprehend academic work and the purpose of education undermined in much the same way today’s students have — by moving through a system that has reduced education to edutainment, and rewards the kind of black-and-white thinking that smartphones are perfect for addressing.

It’s Time to Listen to the Teachers

The teachers that I work with daily — and the teachers that I have interviewed across the country over the past decade — are generally in agreement that the nation’s rabid focus on test scores have had a deleterious impact on education and what it should be.

Not simply the memorization of facts and the mastery of skills — though these are important — but developing intellectually nimble adults who are ready to face the ever-changing world they’re inheriting.

Standardized testing has utterly failed us in this regard. When learning is geared to the test, then all that is taught is the test. The real work of education — learning to think independently, to struggle with complexities in the sciences and the liberal arts, and to begin to wrestle with age-old problems about what it means to be human — is sacrificed.

Smartphones are similarly one-dimensional. They deliver just-the-facts information that students and adults to too poorly prepared to assess and use effectively.

Where does this leave us?

First — by all means, ban cellphones in schools. The social, emotional, and learning damage caused by smartphones — namely, an inability to interact in healthy ways with the people around them — is well-documented, as are the negative impacts on learning.

The simple act of plying kids’ dopamine toys from them will force them to do hard things, like understand the complexities behind the ideas they increasingly encounter as they reach high school and college.

Second — we adults have to reckon with our own use and abuse of these tools.

As a society, we have become addicted to our smartphones. The phone itself is not the problem. Like so many things, it’s a tool. On this point, Horn is correct about the power of technology to make us more creative people.

But to use this tool effectively, we must first have the intellectual heft and the self-discipline to use smartphones as a tool, and not a crutch.

From the front of the classroom, day-in-and-day-out, it was apparent that the vast majority of my students used smartphones as intellectual and emotional crutches.

And from my position as an observer of human activity in general, it’s becoming increasingly clear that our students are using smartphones as crutches because the adults in their lives are doing the same.

Building nimble, creative minds happens best when it happens in live, back-and-forth discussion with others. And it happens when we free teachers to lead the hard, open-ended discussions that education requires.

Banning phones creates the necessary conditions for this to happen. Banning phones in and of itself, however, won’t solve the deeper issues that now plague education.

Yes, smartphones are failing all of us. But high-stakes standardized tests have proven conclusively over the past quarter century that they, too, are failing us. In fact, they are as damaging as smartphones.

What is needed are not more simple fixes to our testing woes — that’s what smartphone bans essentially promise. Rather, we need a new discussion about the role and purpose of education and how that’s delivered.

That won’t happen, however, until we all put our smartphones down.